My Turn: To a man with a hammer, every problem is a nail

| Published: 11-13-2023 4:09 PM |

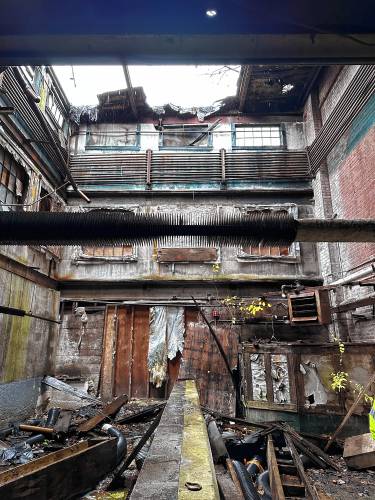

As an urban renewal professional, I can honestly say there was little in the 2022 master plan for the Strathmore complex in Montague that I could get behind.

Developed by Dietz Architects of Springfield, the final vision for the site proposed its near-total demolition, with retention of select wall fragments for “historic interpretation.”

This work did not appear to seek adaptive reuse, nor did it reflect the reality of our already abundant access to nature. Above all, it was a poor option from environmental and economic vantages, incurring multiple rounds of capital-intensive spending — first to demolish, then to remediate, and again for ongoing maintenance — all while eliminating future avenues for Montague to generate income.

Yet within that master plan, Building No. 11 was highlighted as one of the few buildings recommended to be salvaged.

Now, with the carrot of federal brownfield funding on offer, Montague town officials have deemed it beyond repair. In many ways, it’s not their fault. To a man with a hammer, every problem is a nail.

The scope of available funding reflects the ongoing failure of our funding agencies to provide support that is proportional, responsive or in any way strategic. Past rounds of funding have been piecemeal and shortsighted at worst, cosmetic at best, leaving critical issues such as site access and the physical fabric of the buildings unaddressed.

Perhaps most striking is that in autumn last year, just as the master plan was concluding, MassDOT announced plans to invest up to $56 million in the replacement of three bridges across the site within the next decade. None of this investment appeared to take a holistic view of the Strathmore into consideration. Nor was the funding leveraged as a potential bargaining chip during recent negotiations with FirstLight around the renewal of their 50-year license, missing a once in a lifetime opportunity to explore use of the bridge at Rear Canal Road as part of a one-way circular vehicular route through the site.

On the National Register of Historic Places, the Strathmore buildings sit at the heart of one of the few surviving examples of a planned industrial community at this scale. It goes without saying that their erasure represents an enormous loss in its own right.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

1989 homicide victim found in Warwick ID’d through genetic testing, but some mysteries remain

1989 homicide victim found in Warwick ID’d through genetic testing, but some mysteries remain

Fogbuster Coffee Works, formerly Pierce Brothers, celebrating 30 years in business

Fogbuster Coffee Works, formerly Pierce Brothers, celebrating 30 years in business

Greenfield homicide victim to be memorialized in Pittsfield

Greenfield homicide victim to be memorialized in Pittsfield

Real Estate Transactions: May 3, 2024

Real Estate Transactions: May 3, 2024

Battery storage bylaw passes in Wendell

Battery storage bylaw passes in Wendell

As I See It: Between Israel and Palestine: Which side should we be on, and why?

As I See It: Between Israel and Palestine: Which side should we be on, and why?

However, redeveloping even a fraction of the 245,000 square feet of existing floor space in the mill complex holds transformative potential. According to past feasibility studies, Building No. 11, with a footprint of just over 30,000 square feet, was alone anticipated to support 20 housing units and generate an additional $90,000 in annual tax revenues.

Now imagine the impact of 100 additional households and workshop units in a new thriving waterside neighborhood — their purchasing power bolstering the venues, shops and restaurants of Avenue A, and providing tens of thousands in additional tax revenue annually.

From an environmental perspective, total demolition is also a staggeringly wasteful approach. Up to 50% of carbon output in construction projects is generated through manufacturing and transport of raw materials. A brick complex of this scale would host an estimated 8,000 tons of such “embodied carbon” in its structure, foundation and envelope alone. For perspective, to offset 8,000 tons of carbon, you would need to plant just under 400,000 trees.

At a time of climate crisis and spiraling material costs, why are we consenting to adopt such a blunt tool? Because it is the only one on offer.

What we need is public funding that addresses the true obstacles that have caused Strathmore, and countless sites like it, to remain “undevelopable.” This includes funding which:

■De-risks the site for potential developers with packages to cover the burden of Massachusetts building code requirements (elevators, sprinkler systems) that push redevelopment costs beyond levels developers are able to absorb.

■Provides resources for non-capital costs, such as legal mediation.

■Supports facade retention, to retain historic and atmospheric qualities of the structures while allowing for their future use (a common approach in Europe).

Derelict industrial buildings like those in the Strathmore have been central to the transformation of many post-industrial, economically depressed waterside neighborhoods across the world. Even in a global city like London, the revitalization of long-derelict canal-side warehouses in Kings Cross, central London, was inconceivable to local officials in the 1990s.

No one believed the area would ever economically recover. Yet decades later, those buildings form the heart of what is now one of the most celebrated renewal projects in Europe.

We need to adopt that same patient, long-term approach to stewardship of place now, and go back to the table to demand funding that reflects this perspective.

Wholesale demolition is not the answer. Our industrial heritage, local economy, and community — past, present, and future — deserves so much better.

Olivia Tusinski is an urban strategist working in the Economic Development Team at the Greater London Authority, where she directs programs focused on institutional innovation and inclusive economic development. She is a native of Leyden and resides part time in Turners Falls.

Guest columnist Gene Stamell: We know what we know

Guest columnist Gene Stamell: We know what we know Michelle Caruso: Questions candidate’s judgment after 1980s police training incident

Michelle Caruso: Questions candidate’s judgment after 1980s police training incident Kathy Sylvester: Vote for expertise on May 6

Kathy Sylvester: Vote for expertise on May 6 Shirley and Mike Majewski: Vote for Blake Gilmore

Shirley and Mike Majewski: Vote for Blake Gilmore